The Last Word on Mum, by Pema Monaghan. Published by Takeaway Press, 2019. Available for purchase here.

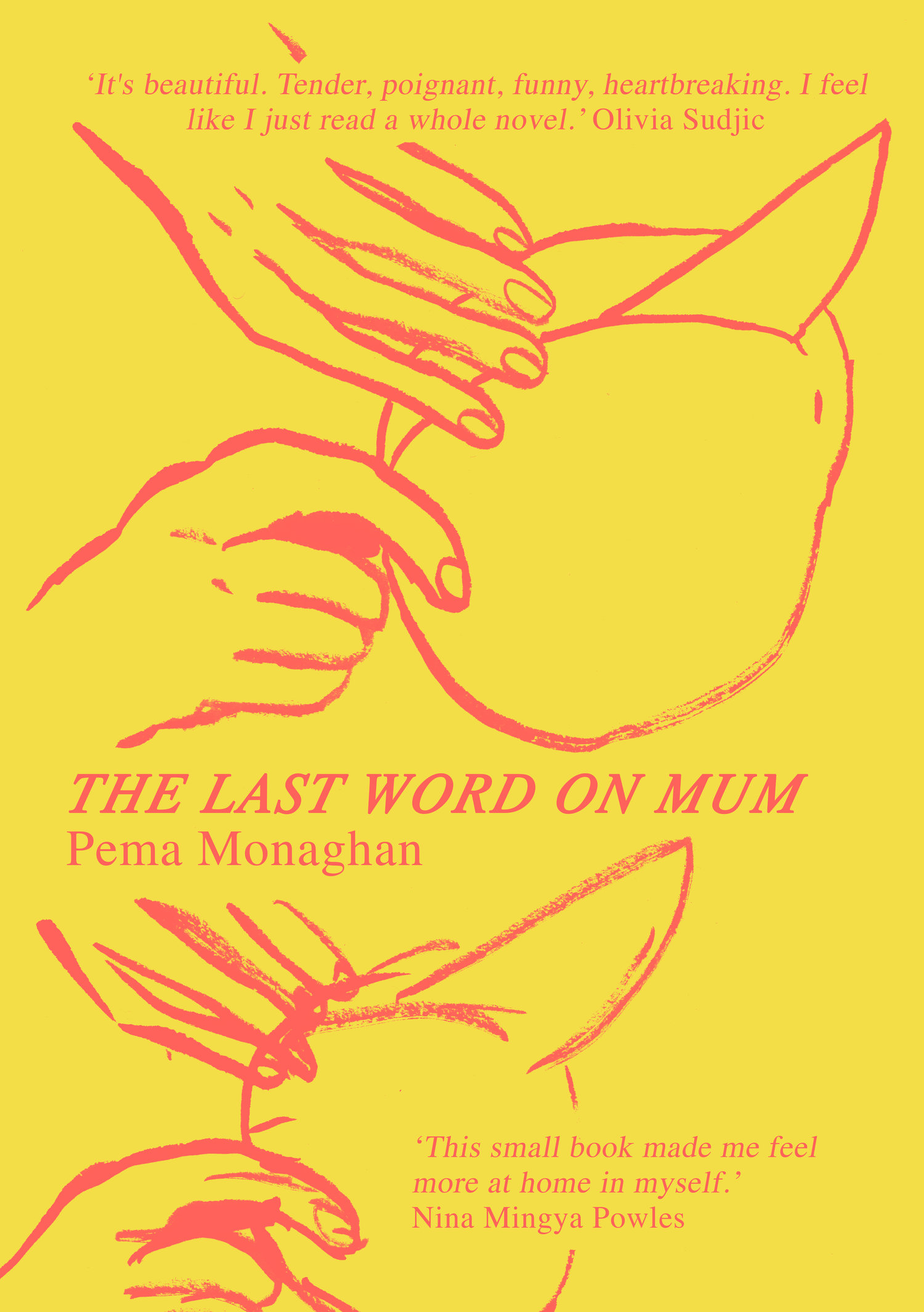

The Last Word on Mum is riso-printed in delicious shades of red and yellow. Colours that would paint a child’s primary memory of sunshine, sand, condiments splashed on food. This is a pamphlet-length poem by Australian writer and journalist Pema Monaghan, illustrated by Oscar Price and hand-stitched with mint-green thread, published by Takeaway Press. With lovely economy, it covers the process of growing up and apart from your mother, who may or may not have first served you that sunshine, sand or condiments splashed on food. There is a directness to Monaghan’s voice which is like a very cold sip of lemonade or pinch of spice. She sweeps us over years of family history in vivid, playful fragments that leave us trying to weave together the state of her maternal relationship. Everything is grounded in the physical: acts of cooking and craft and hiding in bed, the threat of disease, the massaging of babies’ heads, pregnancy, garments and food. Somehow you glimpse the story of lives entwined, then unwinding, and you feel both joyful and sorry.

The poem’s first line is ‘She would be waiting’. I think of that ‘would’ as a conditional, happening in the past but also with the lingering sense that the speaker’s mother is still present, potential. She is portrayed as almost wolverine, possessive of her pack: ‘She would gather us in and breathe on us that we were hers, her girls’. She does not speak but breathes; she acts by a kind of appetite, sorrow, primitive instinct: ‘She would cry. She would gobble us down’. A lot of the poem is really about hunger. The speaker recounts a memory of staying home from school in bed with her sisters, their mother reading ‘My Year of Meats, by Ruth Ozeki’ – a novel that comments on the differences between Japanese and American culture, that looks at hormones in the meat industry and other hidden, sordid facets of society at the turn of the millennium. Opposite this page, there is a photo of the young speaker eating a meal and looking at the camera with a child’s knowing expression of being looked at. You can’t sort the curious from the coy. And so the mother is present by fact of the girl’s look, her wariness, her quiet acknowledgement. You wonder who is most hungry, and for what kind of love, attention or acceptance.

The title The Last Word on Mum evokes the notion of argument: who gets to have the last word, and the power games involved in deciding this final voice. The poem provokes you to think about the act of writing as a mode of ‘tying up’ history. There are images of girls’ hair ‘braided too tight to our scalps’ and ‘detangling potions’ used on ‘unruly tresses’. If the title suggests that the poem moves towards closure, a kind of farewell to the speaker’s mother, the actual poem resists that closure. Monaghan’s short sentences are loose threads, memories: ‘She drove us to tennis’, ‘She made friends with the other mothers’, ‘She kissed us’. Many of these clauses are simply stated, not commented on. The speaker falls between conclusions:

I feel bad for her.

But also, do I have to be the one to take care of her if she gets

a really bad disease?

The poem makes space for resentment, the necessary distance required to mature and break free, while retaining a daughterly conscience. As she grows older, her mother harshly judges or rejects her reading choices (Dracula), the time spent with her aunt, her boyfriend. Quite plainly she says to her mother, down the phone: ‘If you cannot talk to me nicely, we will not say anything to each other ever again’. Maybe this poem is a way of ‘talking nicely’. It is a line thrown out, as a telephone line, a connective gesture. Replying to herself, the speaker adds ‘And we didn’t, so / The jury is still out on if I am a bad, or good, or any sort of / Tibetan girl at all’. There remains this space between mother and daughter, past and future. Identity is something fraught and unfinished, fugitive. It’s there in the tenderly described memories of ‘chapatis with butter, chapatis wrapped around potato curry, chapatis with honey’. Despite writing in some sense ‘against’ her mother, the speaker is not bitter. There is a sweetness to her pared-down lines. She bears patience, guilt, clarity of will. The illustrated loop that closes the pamphlet might imply a sort of closure, but elsewhere the loop is part of a continuous thread we can attribute to writing, writing as a way of reaching out, of showing return. This is the way we were, the way I am now.

The poem is book-ended with scenes from the soft-hued ‘lilac bedroom’ of childhood. As the mother entered the poem, waiting, we exit the poem with an image of the speaker’s ‘sisters and I […] in the lilac bedroom’. This lilac bedroom belongs to ‘Chunyi’, one of the sisters. Things have seemingly changed. This room ‘is the one we wait in most often. We are waiting on the bed for mum to come and find us’. The rigid sentiment of an older generation is replaced by the earnest consolation of the younger, waiting for the older to come back afresh, welcoming. Or is it that only the child versions wait in the dreamlike lilac bedroom, for something impossible, always only to-come? Writing is the space of interval, intimacy, intersection. I wonder if this pamphlet, The Last Word on Mum, is a kind of ‘fourth space’, described by Sandeep Parmar and Bhanu Kapil in Threads (Clinic, 2018) as a place of ‘overlap’, empathic narrative, flickering hospitality and woven experiment in which voices are shared – ‘not a where but a for/u/m’. While the mother has a relatively fixed idea of what ‘Tibetan girls’ do, the speaker highlights her discomfort with that identity, while forging her own cultural associations from childhood memory. With Oscar Price’s gorgeous brush and ink line-drawings of baby faces, mangoes, trees and working hands, there is a sense of ‘taking care’ that suffuses the poem. The illustrations and text interweave real and imaginary stories that fill the fraught landscapes of daughterhood, making space. ‘I know she is real’, the speaker relates of her mother, even if ‘I wish I had dreamt her’. If yellow is a happy colour, red is passion. Is this anger or fervour? It is not a blood-red, but the rich red of a fruit. There is something raw in these lines, but somehow their withholding, their stark unfolding of events, feels generous in its earnestness. In the fourth space of this book, there is space to breathe, to be held in loose and gestural lines. You sense a flourishing, and hope it is mutual.

Maria Sledmere is a practice-based PhD candidate at the University of Glasgow. Developing creative-critical responses and hybrid approaches to aesthetics and everyday life in the anthropocene, she works across visual art, sound, literature and theory. Maria is a member of A+E Collective, freelance music journalist and editor at SPAM Press, Dostoyevsky Wannabe and Gilded Dirt. Two pamphlets have recently been published, lana del rey playing at a stripclub (Mermaid Motel, 2019) and nature sounds without nature sounds (Sad Press, 2019). Her poem ‘Ariosos for Lavish Matter’ was highly commended for the 2020 Forward Prize for Best Single Poem.